Chapter 1

Thursday, Midday

Of course, I hadn’t wanted the money to end up in my account. But now it was there. Why complain? As long as I didn’t spend it, I could return it at any time. Even with interest.

0,8 percent over two months, that made what?

Anyway, if the company had invested the money in a failed project, it would have been lost. Seen that way, it wasn’t in bad hands with me. And as long as no one claimed it, it would just sit there, collecting interest. No one was harmed. And if someone did ask for it back, then fine. I hadn’t asked for it. It had been their mistake. Imagine: I hadn’t checked my account and had spent the money, believing it was mine. Suddenly, I’d have been in debt to the company. That wouldn’t have been fair. A debt caused by their mistake, with no way to work it off.

These thoughts had crossed my mind that morning as I was passing my time by the window. At four o'clock sharp, I was supposed to stop by my old company. The accountant had called me but had remained vague. Admittedly, I hadn’t asked for details. It could only be about the money. Five thousand euros so far. I had no problem returning them. It had never been my money.

True, the security had been a cushion. I had to laugh: I was being too dramatic. I would find a job again. Eventually. Soon. I just hadn’t had any luck so far. The woman at the employment agency had been friendly. Three months to look on my own, with full benefits. I only had to notify them if I left town. (An extended stay outside the city counted as vacation, which would negatively impact my benefits.) So, I was living on unemployment plus an extra two and a half thousand euros a month, through no fault of my own. Maybe I hadn’t found a job because I’d felt too secure, because I thought there was no rush.

The accountant was surely ashamed. Her superiors probably knew nothing of her mistake. She wanted to correct it quietly. So, no harm done. I would return the money, and things would be clear again. Sure, rent was high, but that wasn’t the issue. My savings weren’t much either. Still.

After breakfast -- bread, coffee, half a cigarette by the window -- the nausea came. A constant undertone in the background. Gradually, I was no longer sure if things were really as I had laid them out for myself.

I clicked on the news.

War and politics first, then the local reports. A courtroom here in the city. A defendant, shrunken in on himself. The nameless bank clerk had embezzled hundreds of thousands. Calm images. His desk. His arrest. Everything quiet. The bank director spoke. A longtime employee, he said, someone who had understood the system; who had taken money from clients, invested it speculatively, skimmed the profits, and transferred the original sum back.

A new image.

The defendant in the dock.

His feet didn’t touch the ground.

The press called him Thumbelina.

What a ridiculous figure.

But guys like him are the real perpetrators!

They steal, they rob, making anyone who really needs money look bad. Now others would decide his fate. The verdict was expected next week. Until then, he remained free. An ankle monitor, probation.

Probation -- to prove. How could he still prove himself now?

Five thousand euros wasn’t much for a mid-sized company. How often were larger sums burned through production errors or failed campaigns? But five thousand euros wasn’t nothing either. It was enough to raise questions. To look for someone to blame. Maybe they would even go so far as to pin it on an innocent man. An unemployed fool who hadn’t immediately reported the money he’d wrongly received as salary. Maybe they would put him on trial.

The news anchor presented the weather. I didn’t understand a word of it. The words had lost their meaning. Just sounds, fading away. A reflection in the screen. A face. A man stuck in the small frame. Sticky eyes, sallow skin. Hair slicked to the side. I felt disgust. Inbred ape in a suit. He wasn’t me. Not truly. He was suffering. Writhing. Father would have said:

Meaning: Work, stay out of trouble, and you will be rewarded with a quiet life.

Was this my reward?

I regretted breakfast.

No matter how I looked at it, my behavior wasn’t spotless. Five thousand euros wasn’t enough for prison. But a legal battle was enough to wipe out my savings. The legal fees. Suddenly, a negative balance in my account. Years of work, wasted. And if a future employer ever checked my record ... that alone could ruin my chances. That was the end of my hope. I paced the apartment, aimless, pessimistic.

This morning, time had seemed to stand still. The sun had crawled over the rooftops, never quite reaching its peak. Now it moved unstoppably. Already past the window frame, already on its way west.

I sat still, as if that could stop it.

I calculated: I’d need fifteen minutes. If I left now, five minutes buffer. But then a minute passed, then another. Now I would be on time, but without a buffer. Another minute. Now I’d have to run. Thirteen minutes. Another. Twelve. Even at a sprint, I’d be late now.

A strange thought. As if I had crossed a threshold. I could no longer be on time. And because that was the case, I could just as well wait another minute.

There was something calming about that. At the same time, my body tensed, as if holding its breath. Then I got up and left the apartment. Not to go to the appointment. Just like that. Without thinking. Something was taking shape, an unclear urge.

***

.png)

.png)

In the stairwell, the girl sat on her step, just below the landing to the second floor. The landlord’s daughter. Always alone, never in the mood to talk. She was seventeen, maybe eighteen. But immature for her age. Cheeky, moody. I didn’t like that about her. It reminded me of the past, when girls had something wicked, something frightful about them, even though they were supposed to become women.

She looked at me. Then she looked away.

Her feet were bare, black with dust from the stairwell. It didn’t seem to bother her. But it drove me crazy. I couldn’t stand dirty feet.

"Isn't it cold?"

She nodded, then shook her head. As if the question were a trap.

I glanced at my watch. I had to go.

And yet: "Isn't it cold?"

That’s what you ask as a

neighbour. Yes, I believed I

would have been a good father.

"No," she answered.

"And your soles, they’re completely black."

She looked down, absentminded.

"Where are you going?" she asked.

"To work."

She remained silent, so I kept talking.

"I have to sort something out. I quit."

"Then why are you going to work?"

I shrugged.

"They can’t order you around anymore."

"No," I admitted. I rubbed my palms against my pants. The nausea wasn’t horrible. But it was there. Not inside me, around me, like a gas.

"But one still has to go. That’s just normal."

"And what if you don’t?"

I could have said: Then nothing would happen. But that probably wasn’t true.

"One has responsibilities," I said. "To set things right."

My father would have said that. Sometimes I was startled by how much I sounded like him.

She didn’t let up. "But what if you don’t want to? They can’t force you."

I thought about it.

"Some things have to be done," I said finally. "Even if you don’t want to. And for that, you’re rewarded. With a clear conscience."

Then I left. Down the stairs. Leaving her behind.

***

.png)

.png)

_edited.png)

Slowly, I fought my way up the street, pushing against an invisible resistance. Each step pressed the cold air deeper into my throat, exhaust fumes burrowed into my stomach. The world blurred. Head tucked in, I shuffled along with the rhythm of the others.

The sun was now a pale stain behind a glaring grey wall. Framed by colorless buildings. All strength drained from my legs, and a certainty washed over me, of something dark that was waiting for me. Something with the power to throw my whole life off course and wound me deeply.

A bell struck four. My insides were expanding to an uncomfortable size.

What now?

Leave, disappear. Run until the whole thing was forgotten. I could. In half an hour, I’d be at the airport. I wouldn’t miss my things. South America. Two years, and it would all be erased. I could keep the money. (If you flee, it’s only fair that you get to keep the money.) Who would find out? Who would care?

A woman somewhere in Latin America. A simple life.

And then?

A bitter laugh escaped my mouth. I was too old for fantasies. And I had had my chance at life, I had made all the same decisions everyone gets to make and I had chosen all of them wrong. Aside from that, I wasn’t even allowed to leave the city. That’s what the woman at the job centre had said. And aside from that, the accountant – also a woman, by the way – had called our meeting a formality. I rubbed my hands against my pants. If only I knew whether she would blame it on me or on herself. I would have to be hard on her from the start. Only the guilty fold under pressure.

My phone rang. It was her.

I gripped the lamppost. The nausea surged through me like a heavy current, tossing me back and forth. People pushed past. I swayed.

That damn accountant, that number-cruncher. What was her right to accuse me? Her small-minded grasp of money and numbers? She demanded that I come to her. Who was she to make such a demand?

I lit a cigarette. The city slowly closed in around me. And again, the thought that everything was lost.

What was lost? What had I lost?

I kept walking. Just kept walking.

***

.png)

.png)

At Bismarckplatz, the headquarters loomed. A square building, dotted with small windows. The next gust of cold wind pushed me inside.

Like a defendant dragging heavy chains, I trudged through the lobby, bent under the fear of punishment. I clutched my phone tightly in my pocket, afraid it might ring again and shake me. The nausea seemed to be eating me away from the inside. Maybe it was an ulcer. I was sure it was an ulcer.

Frau Irler wasn’t at her post to receive me for my appointment. That was strange. She usually had everything under control here, an unshakable presence. In her place sat an odd man, in his early forties. He lifted his head and pulled his face into a tragic grimace.

"Frau Irler," he said, "Died a week ago."

It was strange. She had been alive. And now she was dead. Maybe it wasn't that strange. But the young man spoke with the solemnity of a priest leading a service and so everything seemed stranger than it had to be. He thought death was something dignified.

He asked if I had known her well.

"Yes," I said. Most of the time, I lied out of politeness. This time, I lied out of defiance.

I mimicked his grimace, shook my head and murmured to myself how terrible all this was. Really, it is the only right thing to do in such a situation.

In the end, he informed me that:

.png)

The elevator is broken.

He said it with the same bad news bearing face.

The accused had to drag himself up the stairwell, chains and all. Each step drove the nausea deeper into my body. It pressed against my throat, against my stomach, filled my chest. The people passing by were pale shadows, continuing work without me. They didn't seem to mind both that I was here and that I wasn't there.

With every step up, I became smaller. I shrank, lost myself. It was as if I were slowly disappearing. As if, with every step, I breathed less, took up less space. Until only the nausea remained. I pulled myself up by the railing.

On the third floor, an old colleague waved at me, a silent exclamation in his eyes. I saw it there: He knew. Everyone knew. I was being led to the slaughter. And yet, I kept walking. In my pocket, I clutched my phone. It could ring again. I wouldn’t be able to bear it.

They say you should confront your mistakes. No one should carry old burdens into a new life. The weight on my shoulders. This whole building, each step pushing me down.

The hallway stretched endlessly. 401, 402, 403. My destination: 411.

***

I knocked.

"Come in," said a bureaucratic voice.

There sat a woman in a black robe, a white collar. Thin, no discernible breasts. Dry eyes behind thick glasses, reflecting columns of numbers. Why didn't I know her? I knew I should have mingled better.

First, she checked her watch. Then she looked at me.

"You’re late," she said with hanseatic precision. "I called you. Why didn’t you pick up? You know how this works."

Her gaze drilled into me. I felt my heart stumble, skip. I had to tell her. Really, I knew I had to.

"This won’t take long," she said, motioning toward the chair.

I sat down.

Before I could open my mouth, she kept talking: "The resignation. Month before last."

A rush of words escaped me. The past months had been a plague, pure chaos. The bureaucracy, unemployment applications, forms, deadlines. I hadn’t even really expected to move on. It had just happened. An impulse I couldn’t explain. An accident.

"Calm yourself," she said, flipping through her files.

"This is just about the outstanding money."

My foot knocked over a stack of files. Two binders crashed to the floor.

"Watch out!" she snapped.

I knelt down, gathered the papers.

The nausea surged into my nose. I could barely breathe.

"Leave them," she ordered sharply. "Just leave them."

I straightened up. Something stirred in me.

"Frau Irler," I said suddenly.

She raised an eyebrow.

"She was a good woman. Did you know her?"

The accountant looked at me as if I had said something utterly absurd.

"No," she finally said. "I wouldn’t say we worked closely together."

I felt a strange bitterness rising in me.

"But she was a good woman," I repeated, louder this time.

"Yes, I’m sure she was," she sighed. "But right now we need to settle the outstanding money."

I couldn’t let it go.

"Do you know how long Frau Irler worked here?"

"I don’t know." Her tone shifted. "This is about your resignation."

Her voice was getting annoyed.

"But after so many years," I started, "there’s a certain responsibility. You can’t just–"

"You should have given notice sooner," she interrupted.

"I didn’t know I had to," I replied. It felt like the truth.

"It’s about your eight unused vacation days."

I blinked and it seemed as if an incredible calm had settled over the room. I felt the dry ridges of my lips and moistened them with my tongue. Individual flakes of skin had formed. Slowly, they soaked up the saliva and became soft again.

“Your remaining vacation”, she now spoke more forcefully and for the first time I had the feeling that I could understand her. “Unfortunately, we can't pay it out.”

A strange disappointment spread through me.

"Your claim has expired, there is really nothing we can do," she said as if I had asked. There was something pleading in her voice that I now thought might had been there all along.

I nodded cautiously, as if I had to pretend to myself that I understood.

"I just need your signature here," she said. Then she spread out a document in front of me and tapped on some line with her ring finger. Her movements were slow and coordinated.

I signed reluctantly.

Her face brightened and it seemed to me that a great deal of tension fell from her. Her eyes relaxed.

"All done," she said. "I wish you the best of luck."

The door clicked shut behind me.

The nausea changed.

No longer a hot,

sickly-sweet rush.

Instead, it had become a

bitter,

icy

wave

coursing

through

my

body.

In the lobby, a memory overtook me. I remembered a winter’s day. Stormy and cold. I had just came in and brushed the snow from my coat. There was Frau Irler, she embraced a young colleague. The young woman sobbed bitterly, buried deep in the old woman’s arms. It was peaceful and natural, like a saintly image. A scene like a fresco. A moment of such care. Like something from another world.

Suddenly, it seemed very important to me to ask the new secretary when the funeral would be.

"In two days," he answered and handed me a copy of the invitation.

I said that I had valued her greatly. Those words were true and just a little bit of an overexaggeration.

I stepped outside and wind struck my face. No glance back. No further words. With every step, I severed another tie to the past. The building, Bismarckplatz, they no longer mattered. The past had no grip on me anymore.

***

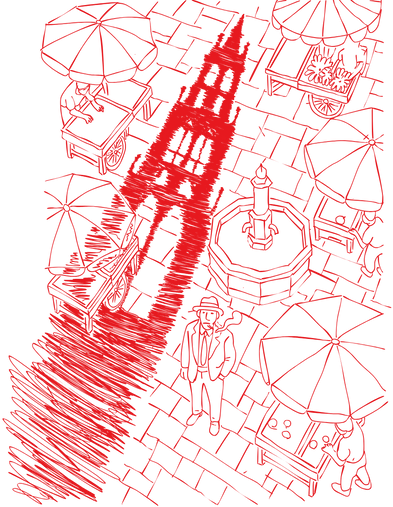

.png)

The gaping mouth of the entrance had spit me out into the world without direction. I stepped outside and felt as if I had stepped out of a decades-long dream. I moved forward. Where to?

I found myself at the market of the church plaza. A handful of vendors remained in these late hours. Their stalls were the remnants of a busy day long gone. Their goods lay forgotten. The vendors talked senselessly, their words echoes of conversations they had repeated thousands of times.

Wilted lettuce and crushed apples littered the ground, trampled by hundreds of shoes. Their scent hovered in the air, sweet or rotten, depending on where you stepped, a mixture of life and decay.

I lit a cigarette. The smoke rose, directionless, swirled, and disappeared. The transformed nausea pressed against my throat. But I kept smoking.

I stopped in front of a display. Turned wooden bowls, smooth polished wood. Should that have been my life? A real trade. A carpenter. Who could look at his work at the end of the day and say: That was me, only me. Wood shavings on the floor, rough hands that caress smooth surfaces, haggling over finished goods. A trade that did not betray.

.png)

And me? I had sat in an office. My place had been interchangeable, my work had left no trace. I had knew everything about the firm and its processes. But the product had been foreign to me: Safety gear. Never would I have needed safety gear. The people at the market, they were part of a cycle. They created, exchanged, sold. And me? I had been a lower employee. I had created nothing, exchanged nothing.

I looked up at the church. The sun hung low, and for a moment, the great stone building looked like it used to.

Then I turned my gaze back to the traders. Their faces were lined, their hands rough from work, their eyes hollow, as if they were looking inward. Their words hung in the air. They were this world, woven into the fabric of their awnings. They were the cobblestones under my feet, the red tables displaying their goods, the wind moving over the market. They were the forest that hid the trees. I was outside of it, not here like they were here. I didn’t belong to their world. I only observed. The nausea divided me.

I moved on. Detached, maneuvering through the passersby. It seemed as if I was the only one escaping their rhythm. A stream of faces without stories, without direction. I was free.

Like a dancer, I slipped past the sluggish, heavy rhythm of the streets. Too many years spent in an office. And now, now I was free. The past was a dream. Had that been my life? God, had I once been married?

The sleepers kept walking. They followed an order that was no longer mine. I followed no order at all. The city was full of chances. Why had I never taken one? All these years I was buried under the weight of obligations, of tasks that weren’t my own. But I was free.

I went down the station. Columns carry the weight of the city, calculated with mathematical precision. No element too heavy, none too light. And yet, could one be removed without everything collapsing?

At Ludwigsplatz, I got off. I stepped back into the evening light. The early evening was clear, as if someone had washed the sky. Dusk stretched thinly over the streets, the shadow pushing the day aside. Even the nausea was gone. Now, it was only freedom raging inside me.

I strolled across the campus. The last light fell on beautiful faces. Young faces, speaking loudly, laughing, certain of themselves. Their carefree energy filled the air. These students had something so beautiful about them: a future still undetermined. In my life, everything had always been decided. Every phase had been predictable. I could be so. I could be part of this world.

***

At the far end of the campus, there was a small gravel terrace, overgrown with ivy. Round tables, glasses filled with spritzed white wine. Students sat there, deep in conversation. Another conversation, that had begun hundreds of years ago and would never end.

With a relaxing sigh, I took the last free table. The sun hung low, and people’s long shadows melted into each other, disappeared, only to reappear elsewhere.

Life seemed so simple when viewed from a distance.

I drank a tulip glass of beer and noticed the blonde woman with peacock earrings smoking at the entrance. A woman, not a student. Late thirties, maybe. I liked long hair on a woman her age. I meant she hadn’t given up her femininity. I liked that about women. Her profile was pretty, her chin curving hollow from her neck with elegant grace, then flattening toward her mouth, giving her face a softness.

I said nothing, just lifted my glass slightly. A quiet gesture that acknowledged the beauty of the evening, the fact that, today, we both existed here, in the same place.

She stubbed out her cigarette, disappeared inside, pretending not to have seen me. It made sense. A woman didn’t like to be addressed from the side. She’d rather leave than endure the gaze of an admirer.

I didn’t mind. Really. It didn’t matter. What could have happened, anyway? Besides, I needed real connection. The secret game of small silences, the quiet complicity of the mind. Without that, sexuality was just discharge.

When Henry entered the bar, he had his phone pressed to his ear. I recognized from his movement that he’d seen me, but he was still talking. He gave me only the slightest signal to follow him. Whether it was one of his sexual conquests or some business executive on the line, Henry always sounded the same. He was indivisible. A hundred years ago, he would have been punished with diseases of the liver, the heart, the flesh. In todays upside-down world, he only seemed to grow healthier.

In the bar, people turned to look at him. He talked without care for the people around him. His fingers indicated that I should sit down and he returned from the bar with two glasses of wine.

I told Henry about the accountant, about how she had summoned me over eight unused vacation days. I demanded outrage from him. But he was distracted.

"Talk to her," he said. "You’re taking her home tonight."

Henry picked women for me without ever letting me in on his thought process. I glanced over. My suspicion was confirmed. She was oh so young. Maybe in her mid-twenties. God, she was a child.

"This is a bad idea," I objected. "She’s probably waiting for someone."

Henry dismissed my words with a flick of his hand. Then his gaze shifted to the blonde with the peacock earrings, smoking again outside by the door. He took a sip from his glass, considered for a moment, and proclaimed: "She’s destructive."

The waitress approached our table. Henry ordered two glasses of wine that he would later demand he should pay. Not because I didn't have a job, he always demanded to pay. The moment she left, he shared his theory about her:

"Women like her always end up as mothers. It’s in their nature. She is just motherly. But now’s the moment to choose the situation. I will tell her when she comes back that she should quit and find a better job. He maternity pay depends on it."

I don't know why he said such things. The thought made me nauseous.

When she finally brought the drinks, he grasped her wrist, pulled her toward him, as if he were her boss and she his secretary. This needs to be on my desk by tonight.

I tried for eye contact to give a silent apology for his behaviour. She didn’t smile.

Henry was aggressive. I was measured. It was an unspoken division of labor. I stayed in the background, apologized with glances and sometimes, that’s how conversations started. Women who were annoyed with him turned to me: the intellectuals (sociology or pedagogy), or the freshly heartbroken, who mistook male restraint for virtue. Their friends – the prettier but more worn ones – played at indignation at first, only to eventually give in to Henry’s advances once their feigned outrage had burned out. The important thing was that the women felt they could convincingly tell themselves the next morning that Henry had deceived them. It was a game without end.

Henry raised his finger, his eternal instructor’s tone. "Go now." His thoughts had returned to the young woman at the other table.

I tried to steer the conversation back. But he took pleasure in ignoring my story about the accountant. Then he started panting like a dog.

"She’s young," I said.

Now Henry was irritated. "What are you waiting for?" he asked. "For her to turn forty?"

I didn’t answer.

"Women over thirty-five," he claimed, "have expectations no self-respecting man can fulfil. The girl is an adult, what's there to discuss? She can say no. And you don't respect her as a woman if you patronize her like that."

I felt anger rise in me. Although I felt that he was right.

"That’s not the point," I said. "You have responsibility."

Henry looked at me with a silly face. His gaze dug deeper and deeper and ridiculed me. He knew these kinds of thoughts and saw them for the excuses they were.

Henry shook his head. "You don’t have to act like that in front of me. And it will surprise you to learn that women don’t respect men who talk like that either. Not really," he said. "Just have some courage."

As if to prove his point, he got up and strolled over to the blonde with the peacock earrings. He leaned over her, spoke for a while. She brushed him off multiple times, but he didn’t let up. She was now buried in a travel guide, holding it up like a shield.

That’s what he got, the damn fool.

I just looked at him coming back to our table. He seemed unimpressed.

Again and again, I shot the blonde with the peacock earrings an apologetic look, until, at one point, our eyes met. But she only looked at me with quiet contempt.

***

It was deep into the night when we left the bar. Henry and I, wandering through the streets in an endless figure eight.

"We’re friends, aren’t we?" he proclaimed.

I agreed silently.

"I’m going to bang the waitress," he said.

Before we had left, Henry had asked the waitress for her number. "Maybe later," she had said. "Why not now?" Henry had asked. She hadn't answered. Henry had grabbed me by the shoulder, pointed at my chest, and explained "he waited to have sex until he was married. Did you ever have sex?" I bit my lip not to shout at him. The waitress got mad too and was about to storm off but Henry played stupid. "Why? Is this too private?" he asked her. She got hung up and began to explain to him the impertinence of his question. "But don't you agree that sex nowadays is something emancipating?" And so it went on, she tried to explain and he asked stupid questions. By the end they had an actual conversation and she explained that she liked sex and – indeed – thought of it as something emancipating. Then she laughed and gave him his number. "We can’t all wait until we’re married," he had said to me at last.

We walked in silence for a moment. Then he added, "She’s not pious either. I know women like that. The waitress is destructive. That’s what makes it interesting. You can’t show that you care about what’s broken, or you’ll lose their attention."

The alcohol pulled at my thoughts. Empty images of the secretary consoling a crying woman.

What happens when she’s destroyed everything?

Henry raised his finger, as if making a final declaration. "Then you need a pious girl again. One who’ll patch you up and take care of you."

I stopped walking.

To hell with Henry. Someone who doesn’t understand you isn’t a friend. I should surround myself with virtuous people. People who rise a torch into the dark sky. Who serve as beacons to one another. Only the highest should surround me, friends who walk free and cast shadows.

At the station, we parted ways. God, how I hated him.

I walked on.

What did he know! The waitress was full of virtue, full of it, or pious as he had said. At the other end of the night, a new morning waited. Beyond sleep, a new freedom. Something more than just the absence of work.

The city peeled itself open in the new morning facades, shop windows, black doorways. A mouth in the dark. A quiet kiss on my cheek. A hand reaching for mine. I declined, politely. Women in rectangles. A sphinx in the narrow pass, waiting to devour me. I would have liked to be devoured.

***

The door slammed shut behind me, heavily and slowly. I should have closed it more quietly, but then it was too late. The light in the stairwell was dim. The steps lay cool, empty, except ... I knew she was there. She was waiting for me, I had no doubt in my mind. There she sat on her step, her bare feet on the stone. Oh, if only I had seen that the door to her father's apartment was open. If only I had...

But no, I was too transfixed. It was as if she had been fused to the house, as if she was a piece of it that wasn't allowed to move, that had to stay in place like a stone chimera.

"Eight days," I said. "Eight vacation days. And do you know what I told them?"

Silence.

"I told them where they could shove them."

I laughed. It wasn’t a friendly laugh, I didn’t know why. Then I looked at her.

"Well?" I said. "What do you think?"

She raised an eyebrow. "Very brave of you."

Something in her tone irritated me and made me mad. I pushed myself off the wall, took a few steps, then turned back to her.

"After that, I was at the bar with Henry," I said. "In case you were wondering why I was gone so long."

She lifted her head, but only slightly.

"He–" I hesitated. "Do you know those people who just take?"

No answer.

"He is like that," I said. "A taker."

I kept talking because the silence wouldn’t let me go.

"But you have to escape. Life runs in patterns. Always the same. Always the same. Everything already decided."

I heard myself speaking, but the words had no clear shape. They blurred, dissolved. They hung in the air.

"You think you’re doing everything right. But in the end…"

I laughed, suddenly it seemed absurd.

"You wouldn’t understand. You’re still so young."

I shook my head.

"And women…"

I looked at her, but she didn’t look at me.

"But of course, that’s not true. You’re still so young."

The girl didn’t move.

"And that’s Henry’s logic," I said. "I don’t think that way.”

I laughed again. My own laughter sounded wrong. She looked at me.

"Your friend sounds charming," she said.

I blinked.

"He calls it directness," I said.

"And you?"

I hesitated.

"What?"

She remained seated, unmoving.

"What do you call it?"

I felt a strange warmth rise inside me, suddenly I felt very drunk.

"I…" cleared my throat.

I wouldn’t have said what came next if she hadn’t been looking at me like that.

"Sometimes, I’d like to smash his skull in."

Then the girl stood up, as if she had recognized a hidden signal. Suddenly we were close.

"What are you doing?" she asked me and seemed surprised.

With the tips of her fingers she shoved me.

"Stop it," I said.

She shoved me again, this time harder.

"Stop it!" My face grew hot with anger.

My heart pounded too fast. I felt the heat in my head, a sluggish, numbing warmth.

I grabbed her wrists, both in one hand. So tightly, I didn’t notice how tightly. I could feel her bones pressing against her skin. Her face twisted. And to my horror there was fear in her eyes. But I didn’t let her go.

With one hand I held her like that and with the other I pinched her side. Between my fingers, I held a tiny roll of flesh. Small and soft but more real than fingers or bare feet. Revenge for the fear in her eyes. That damn brat! This was her fault, not mine.

She let out a short, shrill scream.

Her hands flew to her mouth.

And then, as if set into an automatic sequence, above the girl, the door to her father’s apartment opened. A soft, quiet click. Immediately, the sound of the door turned me into a spectator of my own situation.

I let go immediately.

Then neither of us moved. Not a single millimetre. In that moment, her brattiness disappeared and it became fear of something ominous. But behind her, there was no one. The darkness stared at us through an empty slit. And then, as if returning to the natural order of things, she pulled away from me. She climbed the steps. Slowly.

Not hurried. Without panic, but heavy with something else.

I watched her go.

Then I wasn’t angry anymore. I could not move or speak. What had just happened?

She slipped through the doorway, swallowed by the blackness inside. The door closed.

Then I went quietly up the stairs. I didn’t turn my head as I passed her door. Still I felt that I was being watched.

***

Back in my apartment, a wave of anger washed over me and an inexplicable urge for revenge engulfed me. To punish her. To punish her for this mess, for the restlessness in the world that was my heart, for my tangled situation.

Then, I fell asleep.

_edited.png)

I nearly lost my balance. I leaned against the wall.

"I showed them," I said.

She didn’t react.

"At my old company," I said.

I waited. Nothing.

"It was about my vacation days."

She just stared at me.

.png)