William Dupris · 15 min read · SEASON 1

by W. Dupris

In Hamburg, I entered the sleeper car. Two women shared the compartment with me — one wore a suit and tapped constantly on a corporate tablet, the other had a paper devotional and a bag full of plastic-wrapped meals.

I was planning on tiring myself out with work and then resting my eyes over the night since I can hardly sleep on train rides.

The possibility of my belongings being stolen keeps me half-awake in the night and consequently half-asleep throughout the morning.

Just before departure, the compartment filled with a mix of cleanliness and carelessness—the smell of an old man who still irons his shirts but hasn’t bought a new one in 20 years.

You can tell by the smell of any man whether he is with or without wife.

He was without.

The women fled the train compartment somewhere past Bremen, visibly defeated by the presence of the old man. Rambled paragraphs of his life came off of him, off-topic, occasionally slurred.

My destination was all the way on the other side of Germany, about 9 hours away from Hamburg. Still, I stayed. Out of politeness or perhaps pity. I had work to do anyway. I buried myself in the draft for a story, something my writing partner suggested: a story about an atheist church clerk. I hated the idea! Too clever. Too on the nose.

Meanwhile, the old man had an opinion on everything.

His dispute with city hall ...

... his dog's injured leg ...

... his stupid neighbors ...

... those damn protestors.

The last point especially got to him. The moral corruption of the climate protestors. He spoke as if the train car were a Facebook post, and we were trapped in the comment section.

The old man eventually coaxed my destination out of me. When I said it was the city of Freiburg, his eyes brightened like a conspirator. It was his destination as well. He asked if I knew a businessman named R. who ran a bicycle company. He was looking for him.

I hadn't heard of the man but had heard of the company. I told him he could look up the address on Maps. He couldn't. I told him he could look up the public records (probably at city hall). He couldn’t. In the end, I looked it up for him and handed him the address.

He accepted the piece of paper like a knight receiving a quest.

The old man was fascinated by my ability to use a phone, and I could see in his gaze that he developed a stupid idea to recruit me for his mission. In return, I tried even harder to ignore him and demonstratively popped out the front of my seat into the narrow night-bed.

Now in a good mood, the old man was loudly talking to himself, dropping suggestive hints how I could be helpful to his mission. I gave him the suggestive hint of pretending to sleep.

He said it so many times I couldn’t take it anymore.

I'm going to stop her!

Who?

“Luisa Neubauer!” he said.

The environmental activist. Her name jumped off his tongue like hot coals.

"All this nonsense. I’ve been tracking the weather longer than they’ve been alive.”

He held up a bunch of wrinkled papers. Most of it was stained, some sheets laminated, others curled at the edges like leaves left too long in the sun. He held it aloft with reverence, as if its aura alone could open a door. There was something ceremonial in how he handled the folder. His eyes gleamed with destiny.

“I have notes. Records. It's all here. I’ll show her.”

I had decided not to let my pity pull me into a prolonged and one-sided conversation. While my head was turned away from him, the old man went back to babbling stories about his dog’s injury, his work as a church clerk, then about his dog again and that damned truck that sprinkles salt on icy roads in winter.

Wait.

I sat up again.

“Church clerk?”

Happy to have captured my attention, the old man explained: “I have been operating a small weather station ever since I was a young man, collecting data long before climate change entered the political agenda.”

“No, no, church clerk?”

“I've seen it all coming for a long time now.“

“Please, tell me about your work at the church!”

“What? No, it's terribly uninteresting. I've never had any relation with the church.”

Could he be the man I found too ironic to even let exist in my imagination.

“But you just said that–“

“I heard on the radio about that R. from Freiburg who owns a bike company and who was in contact with Luisa Neubauer, so–“

“So, your work in a church …”

“–I need to meet him and ask him to connect me with Neubauer. This needs to stop!”

“Why do you need Neubauer to stop?”

Damn fool, why did I ask?

He got up and paced around. His steps didn’t cover much distance. Short legs in wide black dress pants that were held up by a tight worn-out leather belt.

What struck me in the conversation that followed was the old man's complete lack of preparation. He had not booked a hotel or had any clue what to do once he got to Freiburg. All he had was an address (that I had given him) and a tuna sandwich.

He had never left the island, not even after the wall fell. Nor after his wife left or after he could not find a job.

He doesn’t carry any modern electronics. Having grown up on ...

ASTEROID ISLAND!

... he relies on his all-weather suit and public broadcasting.

He explained to me that after retirement, all he had left was his dog. His wife was no longer there, nor the kid. And then there was this damn truck which sprinkled salt on the pavement. The machine had hit his dog’s leg because it had driven too close to his property and injured the poor animal. For the rest of its life the dog limped around in fear. But no one apologized. No one owned up to the mistake. It wasn’t like the man wanted to blame anyone. He just didn't want it to happen to someone else.

"You need to be able to trust each other," he said. I could hear the hurt in his voice.

Carefully, I tried to ask him about the church work, but he waved me off.

In an act of desperation, he had gone to war against his town. On an island, everyone knows each other. And everyone works for someone else.

The council, the complaints office, the planning board, they weren’t strangers. They were his neighbours. His butcher, his friend from school, the woman who used to drink coffee with his wife. But when they exercised bureaucratic duties, something happ-ened. They stopped being neighbours. They became officials. And officials don’t apologize.

He filed reports. Demanded inspections. Knocked on doors. The silence thickened. The conflict had taken his dog too. With its tail tucked between its legs, it died somewhere around the time everybody started hating its owner.

With feigned innocence, I tried to steer the conversation back to his work as a church clerk. He sighed, gave me a look like I was the crazy one, and said, "I really don't know why you want to know about that. It don't got nothing to do with anything."

Under the communists, he explained to me, you just had to ask for work.

He had liked building roads. It wore down his body, but it gave him a purpose.

But when the system collapsed, there was no one left to tell him what to do. He was on his own. He took the only job he could find and became a church clerk. A job unsuitable to his hands and senseless to his head.

He wasn't religious. He had grown up in a world without God. Yet, he kept the church open. Maybe that’s all a church clerk really is: someone who performs the rituals ...

... out of habit ...

... out of duty.

He had made it through all of communism without ever losing trust in government or neighbours. Then the wall fell and the government hurt his dog. The old man couldn't stand the injustice. Watching his dog die, he lost his trust in his neighbours, in the government, and in the thin distinction between the two. Neither were there for him. So, he did what any sensible man in his position would do. He radicalized himself.

Without a phone or access to the internet, the old man listened to public radio: In nightly sessions he compared his handwritten weather logs to the findings of the scientists inside the talking box and let his passion burn.

Something had to be done.

He listened. Compared. Calculated. And then he decided:

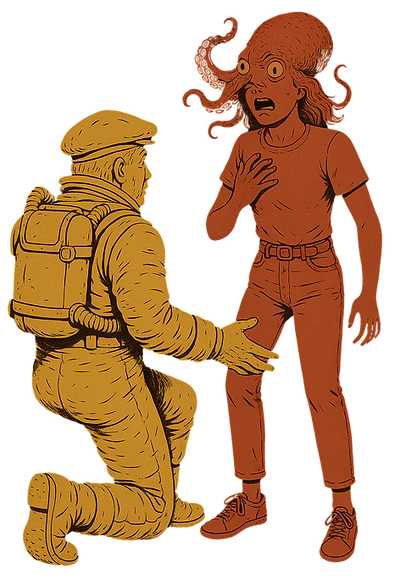

What I came to understand was this: He didn’t reject the protests because he didn't believe in climate change. He rejected them because he did believe in it. He had become obsessed with the idea that only he could stop it.

However, he didn’t understand how protest movements worked. He thought they all followed the neighbourly logic of the island. But of course, a movement is not an island.

“All this gluing their hands to streets. It’s childish. It doesn’t work. I need to tell Neubauer to stop and take over the protests myself.”

I looked at him. A man with a sandwich and a folder, ready to confront a generation.

“You?” I asked.

“It is too serious.”

I asked what he’d do if the businessman in Freiburg didn't want to see him.

“What do you mean?” he said, genuinely puzzled.

“If he’s not there. Or won’t talk.”

“But I have his address?”

I realized that not seeing someone is something that is not possible on a small island.

I wanted to ask more questions about his work as a church clerk, but it really did seem like the least interesting part of his life.

We had talked for over four hours. I had begun to suspect he wasn’t just heading toward a city. He was on a journey. His language was riddled with vague enemies, with misplaced alliances, with a righteousness no amount of reasoning could pierce through. Many things he explained to me three or four times.

But did it really explain his quest?

Then it came to me.

Something else must have happened.

Something he only had mentioned incidentally.

Maybe it was all about them.

We arrived early in the morning.

He wrote down his name and address and said to visit him if I was ever near his far away home. I pointed out the direction of city hall. We shook hands and parted ways.

I went on my way, filing him under “useful character.” I was already thinking about how to describe him. How to describe his jacket, his belt, and his absurd plan.

Then I paused, just long enough to wonder: Had he thought about how he would get back to the north?

He hadn’t.

He wouldn’t.

He didn't need to.

He had cared for the church without believing in it. Now he wanted to take care of the planet in the same way. By sweeping the floors, dusting off the altar, and changing the light bulbs, as if that would be enough.

He couldn't see that he was no longer part of the world he wanted to save. He couldn't see that he had become an island.

.png)

.png)